Richard Mentor Johnson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard Mentor Johnson (October 17, 1780 – November 19, 1850) was an American lawyer, military officer and politician who served as the ninth

About the time of Richard's birth, the family moved to

About the time of Richard's birth, the family moved to

After passing the bar, Richard Johnson returned to Great Crossing, where his father gave him a plantation and slaves to work it. The many lawsuits over ownership of land provided him with much legal work, and, combined with his agricultural interests, he quickly became prosperous.

Johnson ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1803, but finished third, behind the winner, Thomas Sandford, and William Henry. At that time, following the inauguration of

After passing the bar, Richard Johnson returned to Great Crossing, where his father gave him a plantation and slaves to work it. The many lawsuits over ownership of land provided him with much legal work, and, combined with his agricultural interests, he quickly became prosperous.

Johnson ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1803, but finished third, behind the winner, Thomas Sandford, and William Henry. At that time, following the inauguration of

At the battle itself, Johnson's forces were the first to attack. One battalion of five hundred men, under Johnson's elder brother, James Johnson, engaged the British force of eight hundred regulars; simultaneously, Richard Johnson, with the other, now somewhat smaller battalion, attacked the fifteen hundred Indians led by Tecumseh. There was too much tree cover for the British volleys to be effective against James Johnson; three-quarters of the regulars were killed or captured.

The Indians were a harder fight; they were out of the main field of battle, skirmishing on the edge of an adjacent swamp. Richard Johnson ordered a suicide squad of twenty men to charge with him and draw the Indians' fire, with the rest to attack as the Indians reloaded. But he was unable to push his troops through the enemy position due to the swampy ground. Johnson had to order his men to dismount and hold until Shelby's infantry came up. By then, under the pressure of Johnson's attack, the Native American force broke and fled into the swamp, during which time Tecumseh was slain.

The question of who shot and killed Tecumseh was highly controversial in Johnson's lifetime, as he was most often named as the shooter. Johnson himself did not publicly say that he had killed Tecumseh, stating that he had killed "a tall, good-looking Indian", but initial published accounts named him, and it was not until 1816 that another claimant, a man named David King, appeared. John Sugden, in his book on the Battle of the Thames, found that Johnson's "claim is surely the stronger". Jones suggested that the issue did not truly catch the public's attention until Johnson became a potential candidate for national office in the 1830s, and was promoted through such means as a campaign biography, stage play and song. In any event, he found, "Colonel Johnson truly was a war hero at the Battle of the Thames. By ... leading the suicide mission on horseback, more lives were saved than lost. Johnson was lucky to have been only wounded, since fifteen men died instantly during the charge."

There are reports from Indians that support Johnson's account, but most were made decades after the battle, by which time the question of whether Johnson shot Tecumseh had become politically charged. Tecumseh was said to have been shot from a firearm pointed at a downward angle, as if from a horse, with a ball and three buckshot, which Johnson's pistol was said to be loaded with. Evidence that it was so loaded is lacking, and the angle of the wound did not exclude the possibility that he had been stooping when shot. Some accounts have muskets loaded with cartridges containing a ball and three buckshot being commonly carried by American soldiers, and whether the Americans identified the proper body as Tecumseh (whose death was attested to by British officers who had been at the battle) is another source of contention.

On April 4, 1818, an act of Congress requested that the President of the United States present to Johnson a sword in honor of his "daring and distinguished valor" at the Battle of the Thames. The sword was presented to Johnson by President

At the battle itself, Johnson's forces were the first to attack. One battalion of five hundred men, under Johnson's elder brother, James Johnson, engaged the British force of eight hundred regulars; simultaneously, Richard Johnson, with the other, now somewhat smaller battalion, attacked the fifteen hundred Indians led by Tecumseh. There was too much tree cover for the British volleys to be effective against James Johnson; three-quarters of the regulars were killed or captured.

The Indians were a harder fight; they were out of the main field of battle, skirmishing on the edge of an adjacent swamp. Richard Johnson ordered a suicide squad of twenty men to charge with him and draw the Indians' fire, with the rest to attack as the Indians reloaded. But he was unable to push his troops through the enemy position due to the swampy ground. Johnson had to order his men to dismount and hold until Shelby's infantry came up. By then, under the pressure of Johnson's attack, the Native American force broke and fled into the swamp, during which time Tecumseh was slain.

The question of who shot and killed Tecumseh was highly controversial in Johnson's lifetime, as he was most often named as the shooter. Johnson himself did not publicly say that he had killed Tecumseh, stating that he had killed "a tall, good-looking Indian", but initial published accounts named him, and it was not until 1816 that another claimant, a man named David King, appeared. John Sugden, in his book on the Battle of the Thames, found that Johnson's "claim is surely the stronger". Jones suggested that the issue did not truly catch the public's attention until Johnson became a potential candidate for national office in the 1830s, and was promoted through such means as a campaign biography, stage play and song. In any event, he found, "Colonel Johnson truly was a war hero at the Battle of the Thames. By ... leading the suicide mission on horseback, more lives were saved than lost. Johnson was lucky to have been only wounded, since fifteen men died instantly during the charge."

There are reports from Indians that support Johnson's account, but most were made decades after the battle, by which time the question of whether Johnson shot Tecumseh had become politically charged. Tecumseh was said to have been shot from a firearm pointed at a downward angle, as if from a horse, with a ball and three buckshot, which Johnson's pistol was said to be loaded with. Evidence that it was so loaded is lacking, and the angle of the wound did not exclude the possibility that he had been stooping when shot. Some accounts have muskets loaded with cartridges containing a ball and three buckshot being commonly carried by American soldiers, and whether the Americans identified the proper body as Tecumseh (whose death was attested to by British officers who had been at the battle) is another source of contention.

On April 4, 1818, an act of Congress requested that the President of the United States present to Johnson a sword in honor of his "daring and distinguished valor" at the Battle of the Thames. The sword was presented to Johnson by President

''Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture'', accessed November 12, 2013 Another pet project Johnson supported was prompted by his friendship with John Cleves Symmes, Jr., who proposed that the Earth was hollow. In 1823, Johnson proposed in the Senate that the government fund an expedition to the center of the Earth. The proposal was soundly defeated, receiving only twenty-five votes in the House and Senate combined. Johnson served as chairman of the Committee on Post Office and Post Roads during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Congresses. Near the end of his term in the Senate, petitioners asked Congress to prevent the handling and delivery of mail on Sunday because it violated

Johnson served as vice president from March 4, 1837, to March 4, 1841. His term was largely unremarkable, and he enjoyed little influence with President Van Buren. His penchant for wielding his power for his own interests did not abate. He lobbied the Senate to promote Samuel Milroy, whom he owed a favor, to the position of Indian agent. When

Johnson served as vice president from March 4, 1837, to March 4, 1841. His term was largely unremarkable, and he enjoyed little influence with President Van Buren. His penchant for wielding his power for his own interests did not abate. He lobbied the Senate to promote Samuel Milroy, whom he owed a favor, to the position of Indian agent. When

Johnson never gave up on a return to public service. He ran an unsuccessful campaign for the U.S. Senate against John J. Crittenden in 1842. He briefly and futilely sought his party's nomination for president in 1844. He also ran as an independent candidate for

Johnson never gave up on a return to public service. He ran an unsuccessful campaign for the U.S. Senate against John J. Crittenden in 1842. He briefly and futilely sought his party's nomination for president in 1844. He also ran as an independent candidate for

Counties in four U.S. states are named for Johnson, namely in

Counties in four U.S. states are named for Johnson, namely in

Carr also sees, as background motives, the British hostility to slavery, and a consequent wish to disentangle Britain from the United States.

This is chiefly Langworthy's account, but both 300 and 500 men are recorded in other sources.

French is the nineteenth century source, but Berton says it is uncertain which body was Tecumseh's. Few whites had ever seen him.

Today, this would violate the Twenty-seventh Amendment.

Note that Emmons, like Langworthy, was published in New York City.

Richard Mentor Johnson

9th Vice President (1837–1841)", ''Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993'' (

A Biographical Sketch of Col. Richard M. Johnson, of Kentucky

'. New York City, New York: Saxton & Miles. Retrieved on January 3, 2008. * Leyland Winfield Meyer, ''The Life and Times of Colonel Richard M. Johnson of Kentucky''. New York: Columbia University, 1932. OCLC 459524641. * David Petriello, ''The Days of Heroes are Over: A Brief Biography of Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson'' (Kindle edition). Washington, D.C.: Westphalia Press, 2016. . *

Index to Politicians: Johnson, O to R.

Richard Mentor Johnson (1837–1841)

"

"Window to the Past"

Lest We Forget Communications. Retrieved on January 3, 2008. *

By His Hand the Chief Tecumseh Fell

(

The Choctaw Academy

. ''The Chronicles of Oklahoma'' 6 (4), December 1928. Oklahoma Historical Society. January 3, 2008. * James Strange French, ''Elkswatawa'', Harper Brothers, 1836. A historical novel with endnotes based on the author's research and interviews. * Denis Tilden Lynch: ''An Epoch and a Man, Martin Van Buren and his Times'', Liveright, 1929 * Edgar J. McManus,

Richard Mentor Johnson

, ''American National Biography''. Online version posted February 2000, accessed April 5, 2008. * Keven McQueen, "Richard Mentor Johnson: Vice President", in ''Offbeat Kentuckians: Legends to Lunatics'', Ill. by Kyle McQueen,

The Vice-President and the Mulatto

, ''

Johnson, Richard Mentor

, ''Biographical Directory of the United States Executive Branch, 1774–1989''. Greenwood Press, 1990 . Retrieved on January 5, 2008. *Edmund Lyne Starling,

History of Henderson County, Kentucky

'.

Eccentricity at the Top: Richard Mentor Johnson

" ''Americana Exchange Monthly'', January 2004. Retrieved on January 3, 2008. *George William Stimpson,

A book about American politics

" 1952. Retrieved on August 11, 2010.

"An Affecting Scene in Kentucky"

a political print (c.1836) attacking Johnson for his relationship with Julia Chinn, published in ''

Carolyn Jean Powell, ''"What's love got to do with it?" The Dynamics of Desire, Race and Murder in the Slave South'', January 2002, Doctoral dissertation #AAI3039386, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

"Carrying the War into Africa"

an 1836 political print attacking Johnson for his relationship with Julia Chinn, published in ''Harper's Weekly'', at Library of Congress * Richard Shenkman, Kurt Reiger (2003).

The Vice-President Who Sold His Mistress At Auction

, ''One-Night Stands with American History: Odd, Amusing, and Little-Known Incidents.'' HarperCollins, pp. 71–72. . * George Stimpson, ''A Book about American Politics''. New York; Harper 1952, p. 133.

''The Sunday Mail Report''

authored and delivered by Johnson to the Senate on January 19, 1829 (related to delivery of mail on the

Blacks in Appalachia

'. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 1985. pp. 75–80. .

at

vice president of the United States

The vice president of the United States (VPOTUS) is the second-highest officer in the executive branch of the U.S. federal government, after the president of the United States, and ranks first in the presidential line of succession. The vice ...

, serving from 1837 to 1841 under President Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (Uni ...

. He is the only vice president elected by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

under the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment. Johnson also represented Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

in the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

and Senate. He began and ended his political career in the Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form ...

.

Johnson was elected to the House of Representatives in 1806 in the early Federal period. He became allied with fellow Kentuckian Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

as a member of the War Hawks

In politics, a war hawk, or simply hawk, is someone who favors war or continuing to escalate an existing conflict as opposed to other solutions. War hawks are the opposite of doves. The terms are derived by analogy with the birds of the same name ...

faction that favored war with Britain in 1812. At the outset of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, Johnson was commissioned a colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

in the Kentucky Militia and commanded a regiment of mounted volunteers from 1812 to 1813. He and his brother James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

served under William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

in Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the ...

. Johnson led troops in the Battle of the Thames

The Battle of the Thames , also known as the Battle of Moraviantown, was an American victory in the War of 1812 against Tecumseh's Confederacy and their British allies. It took place on October 5, 1813, in Upper Canada, near Chatham. The British ...

. Many reported that he personally killed the Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

chief Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

, a claim that he later used to his political advantage.

After the war, Johnson returned to the House of Representatives. The state legislature appointed him to the Senate in 1819 to fill the seat vacated by John J. Crittenden

John Jordan Crittenden (September 10, 1787 July 26, 1863) was an American statesman and politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He represented the state in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and twice served as Unite ...

. With his increasing prominence, Johnson was criticized for his interracial relationship

Interracial topics include:

* Interracial marriage, marriage between two people of different races

** Interracial marriage in the United States

*** 2009 Louisiana interracial marriage incident

* Interracial adoption, placing a child of one rac ...

with Julia Chinn

Julia Chinn ( – July 1833) was an American plantation manager and enslaved woman of "mixed-race" (an "octoroon" of seven-eighths European and one-eighth African ancestry), who was the common-law wife of the ninth vice president of the United S ...

, a mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-ethn ...

slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

who was classified as octoroon

In the colonial societies of the Americas and Australia, a quadroon or quarteron was a person with one quarter African/ Aboriginal and three quarters European ancestry.

Similar classifications were octoroon for one-eighth black (Latin root ''octo ...

(or seven-eighths white). Unlike other upper-class planters and leaders who had African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

mistresses or concubines, but never acknowledged them, Johnson treated Chinn as his common law wife

Common-law marriage, also known as non-ceremonial marriage, marriage, informal marriage, or marriage by habit and repute, is a legal framework where a couple may be considered married without having formally registered their relation as a civil ...

. He acknowledged their two daughters as his children, giving them his surname, much to the consternation of some of his constituents. It is believed that because of this, the state legislature picked another candidate for the Senate in 1828, forcing Johnson to leave in 1829, but his Congressional district voted for him and returned him to the House in the next election.

In 1836

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Queen Maria II of Portugal marries Prince Ferdinand Augustus Francis Anthony of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

* January 5 – Davy Crockett arrives in Texas.

* January 12

** , with Charles Darwin on board, r ...

, Johnson was the Democratic nominee for vice-president on a ticket

Ticket or tickets may refer to:

Slips of paper

* Lottery ticket

* Parking ticket, a ticket confirming that the parking fee was paid (and the time of the parking start)

* Toll ticket, a slip of paper used to indicate where vehicles entered a tol ...

with Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (Uni ...

. Campaigning with the slogan "Rumpsey Dumpsey, Rumpsey Dumpsey, Colonel Johnson killed Tecumseh", Johnson fell one short of the electoral votes needed to secure his election. Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

's delegation to the Electoral College refused to endorse Johnson, voting instead for William Smith of South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

. The Senate elected him to the vice-presidential office. Johnson proved such a liability for the Democrats in the 1836 election that they refused to renominate him for vice president in 1840

Events

January–March

* January 3 – One of the predecessor papers of the ''Herald Sun'' of Melbourne, Australia, ''The Port Phillip Herald'', is founded.

* January 10 – Uniform Penny Post is introduced in the United Kingdom.

* Janua ...

. Van Buren campaigned for reelection without a running mate

A running mate is a person running together with another person on a joint Ticket (election), ticket during an election. The term is most often used in reference to the person in the subordinate position (such as the vice presidential candidate ...

. He lost to William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, a Whig. Johnson tried to return to public office but was defeated. He finally was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1850, but died on November 19, 1850, just two weeks into his term.

Early life and education

Richard Mentor Johnson was born in the settlement of Beargrass on the Kentucky frontier (present-dayLouisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

) on October 17, 1780, the fifth of Robert and Jemima (Suggett) Johnson's 11 children, and the second of eight sons. His brothers John and Henry Johnson survived him. His parents married in 1770. Robert Johnson purchased land in what is now Kentucky, but was then part of Virginia, from Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736June 6, 1799) was an American attorney, planter, politician and orator known for declaring to the Second Virginia Convention (1775): " Give me liberty, or give me death!" A Founding Father, he served as the first an ...

and from James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

. He had worked as a surveyor and was able to pick out good land. His wife Jemima Suggett "came from a wealthy and politically connected family."Christina Snyder, ''Great Crossings: Indians, Settlers & Slaves in the Age of Jackson'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), p. 42.

About the time of Richard's birth, the family moved to

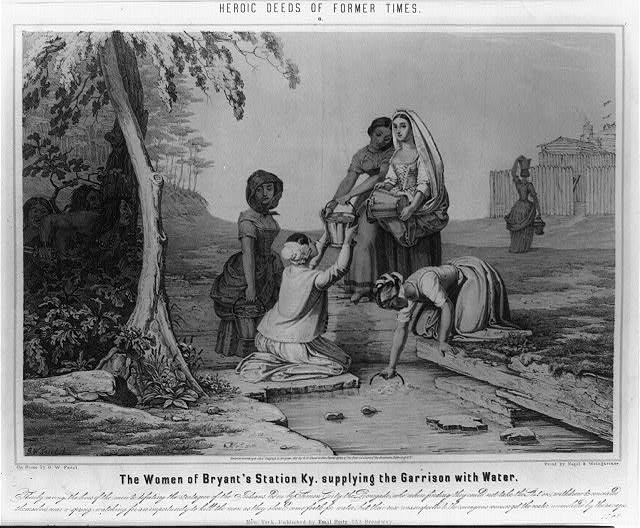

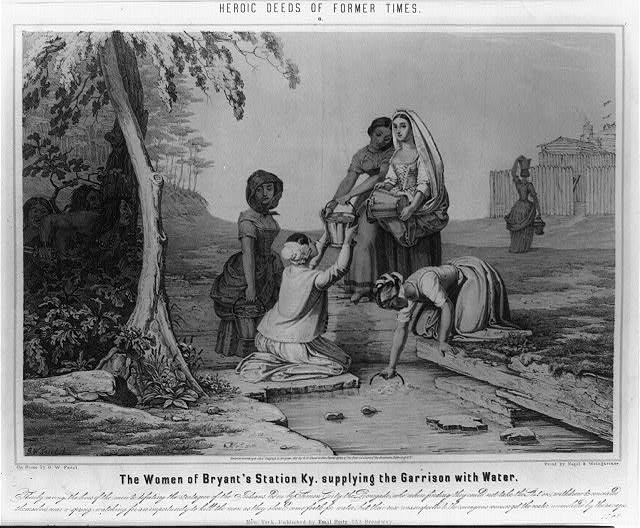

About the time of Richard's birth, the family moved to Bryan's Station

Bryan Station (also Bryan's Station, and often misspelled Bryant's Station) was an early fortified settlement in Lexington, Kentucky. It was located on present-day Bryan Station Road, about three miles (5 km) northeast of New Circle Road, o ...

, near present-day Lexington in the Bluegrass Region

The Bluegrass region is a geographic region in the U.S. state of Kentucky. It makes up the central and northern part of the state, roughly bounded by the cities of Frankfort, Paris, Richmond and Stanford. The Bluegrass region is characteriz ...

. This was a fortified outpost, as there was much Native American resistance to white settlement. The Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

and Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

hunted in this area. Jemima Johnson was remembered as among the community's heroic women because of what was told of her actions during Simon Girty

Simon Girty (November 14, 1741 – February 18, 1818) was an American-born frontiersman, soldier and interpreter from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, who served as a liaison between the British and their Indian allies during the American Revolution. H ...

's raid on Bryan's Station in August 1782. According to later reports, with Indian warriors hidden in the nearby woods and the community short on water, she led the women to a nearby spring, and the attackers allowed them to return to the fort with the water. Having the water helped the settlers beat off an attack made with flaming arrows. At the time, Robert Johnson was serving in the legislature in Richmond, Virginia, as he had been elected to represent Fayette County. (Kentucky was part of Virginia until 1792.)

Beginning in 1783, Kentucky was considered safe enough that settlers began to leave the fortified stations to establish farms. The Johnsons settled on the land Robert had purchased at Great Crossing. As a surveyor, he became successful through well-chosen land purchases and being in the region when he could take advantage of huge land grants.

According to Miles Smith's doctoral thesis, "Richard developed a cheery disposition and seems to have been a generally happy and content child". Richard lived on the family plantation until he was 16. In 1796, he was sent briefly to a local grammar school, and then attended Transylvania University

Transylvania University is a private university in Lexington, Kentucky. It was founded in 1780 and was the first university in Kentucky. It offers 46 major programs, as well as dual-degree engineering programs, and is accredited by the Southern ...

, the first college west of the Appalachian Mountains. While at the Lexington college, where his father was a trustee, he read law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under the ...

as a legal apprentice with George Nicholas and James Brown

James Joseph Brown (May 3, 1933 – December 25, 2006) was an American singer, dancer, musician, record producer and bandleader. The central progenitor of funk music and a major figure of 20th century music, he is often referred to by the honor ...

, later a US Senator.Petriello, pp. 12–13.

Career

Johnson was admitted to the Kentuckybar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

in 1802, and opened his law office at Great Crossing.Kleber, p. 475 Later, he owned a retail store as a merchant and pursued a number of business ventures with his brothers.Hatfield, ''Vice Presidents (1789–1993)'' Johnson often worked ''pro bono

( en, 'for the public good'), usually shortened to , is a Latin phrase for professional work undertaken voluntarily and without payment. In the United States, the term typically refers to provision of legal services by legal professionals for pe ...

'' for poor people, prosecuting their cases when they had merit.Stillman, ''Eccentricity at the Top'' He also opened his home to disabled veterans, widows, and orphans.

Marriage and family

Family tradition holds that Johnson broke off an early marital engagement when he was about sixteen because of his mother's disapproval. Purportedly Johnson vowed revenge for his mother's interference. His former fiancée later gave birth to his daughter, named Celia, who was raised by the Johnson family. Celia Johnson later married Wesley Fancher, one of the men who served in Johnson's regiment at the Battle of the Thames. After his father died, Richard Johnson inheritedJulia Chinn

Julia Chinn ( – July 1833) was an American plantation manager and enslaved woman of "mixed-race" (an "octoroon" of seven-eighths European and one-eighth African ancestry), who was the common-law wife of the ninth vice president of the United S ...

, an octoroon

In the colonial societies of the Americas and Australia, a quadroon or quarteron was a person with one quarter African/ Aboriginal and three quarters European ancestry.

Similar classifications were octoroon for one-eighth black (Latin root ''octo ...

mixed-race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-ethn ...

woman (seven-eighths European and one-eighth African in ancestry), who was born into slavery around 1790. She had grown up in the Johnson household, where her mother served.''Richard M. Johnson (1837–1841)'' Julia Chinn was the daughter of Benjamin Chinn, who was living in Malden, Upper Canada, or London, Canada, and a sister of Daniel Chinn. An 1845 letter from Newton Craig, Keeper of the Penitentiary in Frankfort, Kentucky, to Daniel Chinn, mentions another brother of Julia Chinn named Marcellus, who accompanied Col. Johnson on his first electioneering tour for vice-presidency. Marcellus left Col. Johnson in New York, whereupon Col. Johnson tried to find Marcellus' whereabouts from Arthur Tappan, Esq.

Though Chinn was legally Johnson's concubine, he began a long-term relationship with her, and treated her as his common-law wife

Common-law marriage, also known as non-ceremonial marriage, marriage, informal marriage, or marriage by habit and repute, is a legal framework where a couple may be considered married without having formally registered their relation as a civil ...

, which was legal in Kentucky at the time. They had two daughters together and she later became manager of his plantation. Both Johnson and Chinn championed the "notion of a diverse society" by their multi-racial, predominately white family. They were prohibited from marrying because she was a slave.Mills, ''The Vice-President and the Mulatto When Johnson was away from his Kentucky plantation, he authorized Chinn to manage his business affairs. She died in the widespread cholera epidemic that occurred in the summer of 1833. Johnson deeply grieved her loss.Bevins, ''Richard M Johnson narrative: Personal and Family Life''

The relationship between Johnson and Chinn shows the contradictions within slavery at the time. There were certainly numerous examples that "kin could also be property". Johnson was unusual for being open about his relationship and treating Chinn as his common-law wife. He was heard to call her "my bride" on at least one occasion, and they acted like a married couple. According to oral tradition, other slaves at Great Crossings were said to work on their wedding.

Chinn gradually gained more responsibilities. As she spent much of her time in the "plantation's big house", a two-story brick home, she managed Johnson's estate for at least half of each year, with her purview later expanding to all of his property, even acting as "Richard's representative" and allowing her to handle money. This gave, as historical scholar Christina Snyder argues, some independence, since Johnson told his white employees that Chinn's authority must be respected, and her role allowing her children's lives to be different from "others of African descent at Great Crossings", giving them levels of privileged access within the plantation. This was further complicated by the fact that Chinn was still enslaved but supervised the work of slaves, which the Chinn family never sold or mortgaged off, but she did not have the power to "challenge the institution of slavery or overturn the government that supported it", she only had the power to gain some personal autonomy, with Johnson never legally emancipating her. This may have been because, as Snyder says, liberating her from human bondage would erode "ties that bound her to him" and keeping her enslaved supported his idea of being a "benevolent patriarch".

Johnson and Chinn had two daughters, Adaline (or Adeline) Chinn Johnson and Imogene Chinn Johnson, whom he acknowledged and gave his surname to, with Johnson and Chinn preparing them "for a future as free women". Johnson taught them morality and basic literacy, with Julia undoubtedly teaching her own skills, with both later pushing for both of them to "receive regular academic lessons" which he later educated at home to prevent the scorn of neighbors and constituents. Later Johnson would provide for Adaline and Imogene's education. Both daughters married white men. Johnson gave them large farms as dowries from his own holdings. There is confusion about whether Adeline Chinn Scott had children; a 2007 account by the Scott County History Museum said she had at least one son, Robert Johnson Scott (with husband Thomas W. Scott) who became a doctor in Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

. Meyers said that she was childless.Meyer, p. 322 There is also disagreement about the year of her death. Bevins writes that Adeline died in the 1833 cholera epidemic. Meyers wrote she died in 1836. The Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

notes that she died in February 1836.

Although Johnson treated these two daughters as his own, according to Meyers, the surviving Imogene was prevented from inheriting his estate at the time of his death. The court noted she was illegitimate, and so without rights in the case. Upon Johnson's death, the Fayette County Court found that "he left no widow, children, father, or mother living." It divided his estate between his living brothers, John and Henry.

Bevins's account, written for the Georgetown & Scott County Museum, says that Adeline's son Robert Johnson Scott, her first cousin, Richard M. Johnson, Jr., and Imogene's family (husband Daniel Pence, first daughter Malvina and son-in-law Robert Lee, and second daughter and son-in-law Josiah Pence) "acquired" Johnson's remaining land after his death.

After Chinn's death, Johnson began an intimate relationship

An intimate relationship is an interpersonal relationship that involves physical or emotional intimacy. Although an intimate relationship is commonly a sexual relationship, it may also be a non-sexual relationship involving family, friends, or ...

with another family slave.McQueen, p. 19 When she left him for another man, Johnson had her picked up and sold at auction. Afterward he began a similar relationship with her sister, also a slave.Stimpson, p. 133

Political career

Early years

After passing the bar, Richard Johnson returned to Great Crossing, where his father gave him a plantation and slaves to work it. The many lawsuits over ownership of land provided him with much legal work, and, combined with his agricultural interests, he quickly became prosperous.

Johnson ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1803, but finished third, behind the winner, Thomas Sandford, and William Henry. At that time, following the inauguration of

After passing the bar, Richard Johnson returned to Great Crossing, where his father gave him a plantation and slaves to work it. The many lawsuits over ownership of land provided him with much legal work, and, combined with his agricultural interests, he quickly became prosperous.

Johnson ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1803, but finished third, behind the winner, Thomas Sandford, and William Henry. At that time, following the inauguration of Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

in 1801, many young, democratically minded aspiring politicians were seeking office. While Jefferson and Johnson agreed on the need for greater democracy, Jefferson felt that the people should be led by the elite, such as himself, while Johnson took a more populist view.

In 1804, Johnson ran for the Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form ...

for Scott County (where Great Crossing is) and this time was elected, the first native Kentuckian to serve in the state's legislature. Although the Kentucky Constitution The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the document that governs the Commonwealth of Kentucky. It was first adopted in 1792 and has since been rewritten three times and amended many more. The later versions were adopted in 1799, 1850, a ...

imposed an age requirement of twenty-four for members of the House of Representatives, Johnson was so popular that no one raised questions about his age, and he was allowed to take his seat.Langworthy, p. 9Snyder, p. 44. Seeking to protect his constituents, most of whom were small farmers, he introduced a proposed U.S. constitutional amendment limiting the power of the federal courts to matters involving the U.S. Constitution. Throughout his political career, Johnson sought to limit the jurisdiction of federal courts, which he deemed undemocratic.

In 1806, Johnson was elected as a Democratic-Republican

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

to the United States House of Representatives, serving as the first native Kentuckian to be elected to Congress. In the three-way election, he defeated Congressman Sandford and James Moore. At the time of his election in August 1806, he did not meet the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

's age requirement for service in the House (25), but by the time the congressional term began the following March, he had turned 25. He was re-elected and served six consecutive terms. During the first three terms from 1807 to 1813, he represented Kentucky's Fourth District.''The Political Graveyard''

Johnson took his seat in the House on October 26, 1807; Congress had been called into special session by President Jefferson to consider how to react to the ''Chesapeake''–''Leopard'' affair, the forcible boarding of an American naval ship by a British vessel, with four sailors seized as deserters and one hanged. Jefferson had tried to maintain neutrality with the main combatants in the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, Britain and France, and at his urging, Congress passed the Embargo Act of 1807

The Embargo Act of 1807 was a general trade embargo on all foreign nations that was enacted by the United States Congress. As a successor or replacement law for the 1806 Non-importation Act and passed as the Napoleonic Wars continued, it repr ...

, with Johnson voting in support, finding economic warfare preferable to the use of guns: "we fear no nation, but let the time for shedding human blood be protracted, when consistent with our safety".

Over the following year, Congress attempted to tighten the Embargo, which was widely evaded, especially in the Northeast, with Johnson voting in favor each time. Johnson generally supported Jefferson's proposals, and those of his successor James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

: all three were Democratic-Republicans

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

, and Johnson saw the party's proposals as superior to any suggested by the Federalists

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

, whom he saw as not acting in the best interests of the country. In 1809, Johnson supported Jefferson in adopting the administration's proposal to replace the Embargo Act with the Non-Intercourse Act

The Nonintercourse Act (also known as the Indian Intercourse Act or the Indian Nonintercourse Act) is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set Amerindian boundaries of re ...

, as the Embargo had proven ineffective except in causing a serious recession in the United States.

Although Johnson is considered one of the War Hawks, the young Southern and Western Democratic-Republicans who sought expansion and development of the nation, he was cautious in the runup to the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

. Johnson saw Britain as the major obstacle to United States control of North America, but worried about what a war might bring. By the time Congress met in late 1811, he had come around to war, and joined the War Hawks in electing one of their own, Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

of Kentucky, as Speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** I ...

. Like the other War Hawks, though, he was initially unwilling to support increased taxes and borrowing to finance the construction of naval vessels. When Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war against Britain in June 1812, Johnson voted in favor as the House passed the resolution, 79–49. Madison signed the declaration on June 18, 1812.

For his fourth consecutive term from 1813 to 1815, he had secured one of Kentucky's at-large

At large (''before a noun'': at-large) is a description for members of a governing body who are elected or appointed to represent a whole membership or population (notably a city, county, state, province, nation, club or association), rather than ...

seats in the House. For his fifth and sixth consecutive terms, 1815 to 1819, he represented Kentucky's Third District. Johnson continued to represent the interests of the poor as a member of the House. He first came to national attention with his opposition to rechartering the First Bank of the United States

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

.

Johnson served as chairman of the Committee on Claims during the Eleventh Congress (1809–1811). The committee was charged with adjudicating financial claims made by veterans of the Revolutionary War. He sought to influence the committee to grant the claim of Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

's widow to wages which Hamilton had declined when serving under George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

.Langworthy, p. 10 Although Hamilton was a champion of the rival Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a Conservatism in the United States, conservative political party which was the first political party in the United States. As such, under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801.

De ...

, Johnson had compassion for Hamilton's widow; before the end of his term, he secured payment of the wages.

War of 1812

Initial service

Within a week of the declaration of war, Johnson urged theHouse of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

to recommend the raising of troops in the western states, lest disaster befall settlers on the frontier. After the adjournment, Johnson returned to Kentucky to recruit volunteers. So many men responded that he chose only those with horses, and raised a body of mounted rifles. The War of 1812 was extraordinarily popular in Kentucky; Kentuckians depended on sea trade through the port of New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

and feared that the British would stir up another Indian war. The land war fought in the Northern United States pitted American troops against British forces and their Indian allies. Johnson recruited 300 men, divided into three Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared go ...

, who elected him major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

. They merged with another battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

, forming a regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

of 500 men, with Johnson as colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

, with the merged volunteer forces becoming a brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

Br ...

commanded by General Edward W. Tupper

Edward is an English language, English given name. It is derived from the Old English, Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements ''wikt:ead#Old English, ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and ''wikt:weard#Old English, weard'' "gua ...

of Ohio. The Kentucky militia was under the command of General William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, the Governor of the Indiana Territory.

Johnson's force was originally intended to join General William Hull

William Hull (June 24, 1753 – November 29, 1825) was an American soldier and politician. He fought in the American Revolutionary War and was appointed as Governor of Michigan Territory (1805–13), gaining large land cessions from several Am ...

at Detroit, but Hull surrendered Detroit on August 16 and his army was captured. Harrison by then was in command of the entire Northwest frontier and ordered Johnson to relieve Fort Wayne

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Censu ...

in the northeast of the Territory, which was already being attacked by the Indians. On September 18, 1812, Johnson's men reached Fort Wayne in time to save it, and turned back an Indian ambush. They returned to Kentucky and disbanded, going out of their way to burn Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

villages along the Elkhart River

The Elkhart River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 19, 2011 tributary of the St. Joseph River in northern Indiana in the United States. It is almost entirely c ...

en route.

Johnson returned to his seat in Congress in the late fall of 1812. Based on his experience, he proposed a plan to defeat the mobile, guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or Irregular military, irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, Raid (military), raids ...

of the Indians. American troops moved slowly, dependent on a supply line. Indians would evade battle and raid supplies until the American forces withdrew or were overrun. Mounted riflemen could move quickly, carry their own supplies, and live off the woods. If they attacked Indian villages in winter, the Indians would be compelled to stand and fight for the supplies they used to wage war and could be decisively defeated. Johnson submitted this plan to President James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

and Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

John Armstrong, who approved it in principle. They referred the plan to Harrison, who found winter operations impracticable. Johnson was permitted to try the tactics in the summer of 1813; later, the US conducted Indian wars in winter with his strategy.

Johnson left Washington, D.C. just before Congress adjourned. He raised one thousand men, nominally part of the Kentucky militia under Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby (December 11, 1750 – July 18, 1826) was the first and fifth Governor of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic an ...

, but largely operating independently. He disciplined his men, required that every man have arms in prime condition and ready to hand, and hired gunsmith

A gunsmith is a person who repairs, modifies, designs, or builds guns. The occupation differs from an armorer, who usually replaces only worn parts in standard firearms. Gunsmiths do modifications and changes to a firearm that may require a very h ...

s, blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

s, and doctors

Doctor or The Doctor may refer to:

Personal titles

* Doctor (title), the holder of an accredited academic degree

* A medical practitioner, including:

** Physician

** Surgeon

** Dentist

** Veterinary physician

** Optometrist

*Other roles

** ...

at his own expense. He devised a new tactical system: when any group of men encountered the enemy, they were to dismount, take cover, and hold the enemy in place. All groups not in contact were to ride to the sound of firing, and dismount, surrounding the enemy when they got there. Between May and September, Johnson raided throughout the Northwest, burning the war supply centers of Indian villages, surrounding their fighting units and scattering them, killing some warriors each time.

Battle of the Thames

In September,Oliver Hazard Perry

Oliver Hazard Perry (August 23, 1785 – August 23, 1819) was an American naval commander, born in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. The best-known and most prominent member

of the Perry family naval dynasty, he was the son of Sarah Wallace A ...

destroyed most of the British fleet at the Battle of Lake Erie

The Battle of Lake Erie, sometimes called the Battle of Put-in-Bay, was fought on 10 September 1813, on Lake Erie off the shore of Ohio during the War of 1812. Nine vessels of the United States Navy defeated and captured six vessels of the Briti ...

, taking control of the lake. This made the British army, then at Fort Malden

Fort Malden, formally known as Fort Amherstburg, is a defence fortification located in Amherstburg, Ontario. It was built in 1795 by Great Britain in order to ensure the security of British North America against any potential threat of American i ...

(now Amherstburg, Ontario

Amherstburg is a town near the mouth of the Detroit River in Essex County, Ontario, Canada. In 1796, Fort Malden was established here, stimulating growth in the settlement. The fort has been designated as a National Historic Site.

The town is ...

) vulnerable to having its supply lines cut. The British, under General Henry Procter, withdrew to the northeast, pursued by Harrison, who had advanced through Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

while Johnson kept the Indians engaged. The Indian chief Tecumseh

Tecumseh ( ; October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and ...

and his allies covered the British retreat, but were countered by Johnson, who had been called back from a raid on Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in t ...

that had taken the post where the British had distributed arms and money to the Indians. Johnson's cavalry defeated Tecumseh's main force on September 29, took British supply trains on October 3, and was one of the factors inducing Procter to stand and fight at the Battle of the Thames

The Battle of the Thames , also known as the Battle of Moraviantown, was an American victory in the War of 1812 against Tecumseh's Confederacy and their British allies. It took place on October 5, 1813, in Upper Canada, near Chatham. The British ...

on October 5, as Tecumseh had been demanding he do. One of Johnson's slaves, Daniel Chinn, accompanied Johnson to the battle.

At the battle itself, Johnson's forces were the first to attack. One battalion of five hundred men, under Johnson's elder brother, James Johnson, engaged the British force of eight hundred regulars; simultaneously, Richard Johnson, with the other, now somewhat smaller battalion, attacked the fifteen hundred Indians led by Tecumseh. There was too much tree cover for the British volleys to be effective against James Johnson; three-quarters of the regulars were killed or captured.

The Indians were a harder fight; they were out of the main field of battle, skirmishing on the edge of an adjacent swamp. Richard Johnson ordered a suicide squad of twenty men to charge with him and draw the Indians' fire, with the rest to attack as the Indians reloaded. But he was unable to push his troops through the enemy position due to the swampy ground. Johnson had to order his men to dismount and hold until Shelby's infantry came up. By then, under the pressure of Johnson's attack, the Native American force broke and fled into the swamp, during which time Tecumseh was slain.

The question of who shot and killed Tecumseh was highly controversial in Johnson's lifetime, as he was most often named as the shooter. Johnson himself did not publicly say that he had killed Tecumseh, stating that he had killed "a tall, good-looking Indian", but initial published accounts named him, and it was not until 1816 that another claimant, a man named David King, appeared. John Sugden, in his book on the Battle of the Thames, found that Johnson's "claim is surely the stronger". Jones suggested that the issue did not truly catch the public's attention until Johnson became a potential candidate for national office in the 1830s, and was promoted through such means as a campaign biography, stage play and song. In any event, he found, "Colonel Johnson truly was a war hero at the Battle of the Thames. By ... leading the suicide mission on horseback, more lives were saved than lost. Johnson was lucky to have been only wounded, since fifteen men died instantly during the charge."

There are reports from Indians that support Johnson's account, but most were made decades after the battle, by which time the question of whether Johnson shot Tecumseh had become politically charged. Tecumseh was said to have been shot from a firearm pointed at a downward angle, as if from a horse, with a ball and three buckshot, which Johnson's pistol was said to be loaded with. Evidence that it was so loaded is lacking, and the angle of the wound did not exclude the possibility that he had been stooping when shot. Some accounts have muskets loaded with cartridges containing a ball and three buckshot being commonly carried by American soldiers, and whether the Americans identified the proper body as Tecumseh (whose death was attested to by British officers who had been at the battle) is another source of contention.

On April 4, 1818, an act of Congress requested that the President of the United States present to Johnson a sword in honor of his "daring and distinguished valor" at the Battle of the Thames. The sword was presented to Johnson by President

At the battle itself, Johnson's forces were the first to attack. One battalion of five hundred men, under Johnson's elder brother, James Johnson, engaged the British force of eight hundred regulars; simultaneously, Richard Johnson, with the other, now somewhat smaller battalion, attacked the fifteen hundred Indians led by Tecumseh. There was too much tree cover for the British volleys to be effective against James Johnson; three-quarters of the regulars were killed or captured.

The Indians were a harder fight; they were out of the main field of battle, skirmishing on the edge of an adjacent swamp. Richard Johnson ordered a suicide squad of twenty men to charge with him and draw the Indians' fire, with the rest to attack as the Indians reloaded. But he was unable to push his troops through the enemy position due to the swampy ground. Johnson had to order his men to dismount and hold until Shelby's infantry came up. By then, under the pressure of Johnson's attack, the Native American force broke and fled into the swamp, during which time Tecumseh was slain.

The question of who shot and killed Tecumseh was highly controversial in Johnson's lifetime, as he was most often named as the shooter. Johnson himself did not publicly say that he had killed Tecumseh, stating that he had killed "a tall, good-looking Indian", but initial published accounts named him, and it was not until 1816 that another claimant, a man named David King, appeared. John Sugden, in his book on the Battle of the Thames, found that Johnson's "claim is surely the stronger". Jones suggested that the issue did not truly catch the public's attention until Johnson became a potential candidate for national office in the 1830s, and was promoted through such means as a campaign biography, stage play and song. In any event, he found, "Colonel Johnson truly was a war hero at the Battle of the Thames. By ... leading the suicide mission on horseback, more lives were saved than lost. Johnson was lucky to have been only wounded, since fifteen men died instantly during the charge."

There are reports from Indians that support Johnson's account, but most were made decades after the battle, by which time the question of whether Johnson shot Tecumseh had become politically charged. Tecumseh was said to have been shot from a firearm pointed at a downward angle, as if from a horse, with a ball and three buckshot, which Johnson's pistol was said to be loaded with. Evidence that it was so loaded is lacking, and the angle of the wound did not exclude the possibility that he had been stooping when shot. Some accounts have muskets loaded with cartridges containing a ball and three buckshot being commonly carried by American soldiers, and whether the Americans identified the proper body as Tecumseh (whose death was attested to by British officers who had been at the battle) is another source of contention.

On April 4, 1818, an act of Congress requested that the President of the United States present to Johnson a sword in honor of his "daring and distinguished valor" at the Battle of the Thames. The sword was presented to Johnson by President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

in April 1820. Johnson was one of only 14 military officers to be presented a sword by an act of Congress prior to the American Civil War.

Return to Washington

With the American success at the Battle of the Thames, the war in the northwest was effectively over. Although there was no organized resistance to his presence in Canada, Harrison withdrew to Detroit because of supply problems. Johnson remained, wounded, at Detroit as his men began their return to Kentucky. Once he had recovered enough to bear the journey, he was conveyed home in a bed in a carriage, arriving there in early November 1813. It took him five months to recover, though he was still left with a damaged left arm and hand, and was later described as walking with a limp. He returned to Congress in February 1814, but due to his wounds was unable to participate in debates until the following session of Congress. He received a hero's welcome, still suffering from war wounds that would plague him for the rest of his life. In August 1814, British forces attacked Washington, D.C. and burned theWhite House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

and Capitol, and when Congress reconvened on September 19, with Johnson present, it was in temporary quarters. On September 22, Johnson moved for the appointment of a committee to look into why the British had been allowed to burn the city, and he was appointed as chairman. Johnson's committee compiled a voluminous report, but it was objected to by Representative Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison, ...

, who felt the report, including much correspondence, needed to be printed so that all congressmen could study it. This postponed any debate to 1815, by which time the Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

had been ratified, and the United States was again at peace. With Congress having little interest in debating the matter, it was dropped. Had the war continued, Johnson was ready to return to Kentucky to raise another military unit.

Post-war career in the House

With the end of the war, Johnson, who was made chairman of the House Committee on Military Affairs, turned his legislative attention to issues such as securingpension

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

s for widows and orphans and funding internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

in the West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sunset, Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic languages, German ...

. There were widespread reports of Americans, including women and children, captured by Indians during the war, and Johnson used his congressional office to investigate these matters, and to try to secure the release of captives. Western Democratic-Republicans like Johnson strongly supported the military and urged aid for the veterans; in December 1815, Johnson introduced legislation for the "relief of the infirm, disabled, and superannuated officers and soldiers". Fearing that the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

at West Point, New York

West Point is the oldest continuously occupied military post in the United States. Located on the Hudson River in New York, West Point was identified by General George Washington as the most important strategic position in America during the Ame ...

produced dandies, not soldiers, Johnson expanded on a proposal by President Madison to establish three additional military academies, urging the placement of one of them in Kentucky. Despite the support of such influential members of the House as Clay and John C. Calhoun, the proposal did not pass, but Johnson worked to have federal facilities built in the West throughout his time in Congress.

Johnson believed that Congressional business was too slow and tedious and that the ''per diem'' system of compensation encouraged delays on the part of members.Meyer, p. 168 To remedy this, he sponsored legislation to pay annual salaries of $1,500 to congressmen rather than a $6 ''per diem'' for the days the body was in session.Meyer, p. 170 At the time, this had the effect of increasing the total compensation from about $900 to $1500. Johnson noted that congressmen had not had a pay increase in 27 years, during which time the cost of living had greatly increased, and that $1,500 was less than the salaries of 28 of the clerks employed by the government.Meyer, p. 171 The popular Johnson's sponsorship of the measure provided political cover for proponents; Maryland's Robert Wright wondered how his colleagues would feel if, "the highly honorable mover of this bill, who slew Tecumseh with his own hands ... he who came up here covered with wounds and glory, with his favorite war-horse and his more favorite servant—his attendant in the army, his nurse and necessary assistant" was "obliged to sell his war-horse or his servant"; salaries would prevent such things from coming to pass. The bill passed the House and Senate quickly and was made law on March 19, 1816. But, the measure proved extremely unpopular with voters, in part because it gave Congress an immediate pay raise, rather than waiting until after the next election. Many members who supported the bill lost their seats as a result, including Johnson's colleague Solomon P. Sharp from Kentucky. Johnson's overall popularity helped him retain his seat against a challenge, one of only 15 of 81 who voted to pass the bill to keep their seats in the House. The old Congress met for a lame-duck session

A lame-duck session of Congress in the United States occurs whenever one Congress meets after its successor is elected, but before the successor's term begins. The expression is now used not only for a special session called after a sine die adjou ...

in December, repealed the new law effective when the new Congress was sworn in, but at Johnson's suggestion, did not revive the old ''per diem'', thus forcing the new legislators to act on the matter if they wanted to get paid. Compensation for members of Congress remained on a ''per diem'' basis until an annual salary of $3,000 was prescribed in 1855. According to Edward J. McManus, who wrote Johnson's entry in the ''American National Biography

The ''American National Biography'' (ANB) is a 24-volume biographical encyclopedia set that contains about 17,400 entries and 20 million words, first published in 1999 by Oxford University Press under the auspices of the American Council of Le ...

'', "Johnson, instead of defending the merits of the reform, avoided the backlash by pledging to work for the repeal of his own measure. He justified his reversal by arguing that representatives should reflect the popular will, but lack of political stamina may have been closer to the truth."

Johnson disliked the idea of a national bank, and had voted in 1811 not to renew the charter of the First Bank of the United States

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

. Calhoun's bill for a Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ac ...

passed Congress in early 1816. Johnson was opposed, but was absent for the vote, busy with other matters. A bonus was to be paid to the government by the Second Bank, and a bill was introduced early in 1817 to spend that money on internal improvements. Although Johnson was opposed to the national bank, he supported the bill, believing that the improvements to transportation would benefit his constituents, and the bill passed the House by two votes. Madison, then in his final days in office, vetoed the bill. Johnson joined the effort to override the veto, but it failed. The break from the administration was unusual for Johnson, but he believed the war had shown the need for better roads and canals.

When he took office in 1817, President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

's first choice for Secretary of War was Henry Clay, who declined the position. The post ultimately went to Calhoun. The result was that Johnson became chair of the Committee on Expenditures where he wielded considerable influence over defense policy in the Department of War during the Fifteenth Congress

The 15th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in the Old Brick Capitol in Washington, ...

. In 1817, Congress investigated General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

's execution of two British subjects during the First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

. Johnson chaired the inquiry committee. The majority of the committee favored a negative report and a censure